The case for paying MEPs a whole lot more

“People don’t like their politicians to be comfortable. They don’t like you having expenses. They don’t like you being paid. They’d rather you lived in a f*cking cave” – Malcom Tucker, fictional spin doctor in the BBC’s The Thick of It.

The perks of being an MEP

Transparency International found that in the last mandate, the 30% of MEPs who declared earnings outside their role as elected representatives made a total of €6.3 million on top of their monthly Parliamentary salary (€8,419.90 net).

This raises important questions about side-hustles, for discussion elsewhere. But one striking fact is what we pay this handful of people with so much responsibility and impact on our daily lives.

As far as I can work out (and I may be missing things…) MEPs benefit from:

A monthly wage at 38.5% of an ECJ judge’s salary: €8,419.90. Member States can levy additional taxes on that.

A pension of 3.5% of their salary for each year in office, and one twelfth for each further full month – capped at 70%.

Health insurance.

A transition allowance for up to two years upon leaving Parliament, set at one month’s salary per year in office, rescinded upon employment.

General expenses to cover office rental in their constituency.

€29,557/month for staff. (Which is surprisingly low, given given the demands on them, their domain expertise, their role in greasing the wheels of decision-making, their institutional memory that disappears when they switch jobs, and – for many of them – the untapped potential as future MEPs once they exit the system).

€350/day for each day the MEP is at Parliament: for accommodation, meals and expenses, subject to the MEP registering and attending >50% of the rollcall votes if in plenary.(1)

As far as I can see, they don’t receive:

A bonus tied to performance.

Pay rises for taking on more responsibility.

The infamous Belgian 13th Month salary.

Below is the bull case for paying MEPs a whole lot more.

An MEP’s job is hard…

MPs travel, but MEPs take it to a new level. Next month, a Cypriot MEP is expected to be in Brussels, then Strasbourg, then back in Brussels, then in Nicosia. It poses challenges for those responsible for children and elderly relatives. I suspect it may contribute to why women have never made up more than 40% of a Parliament. It is also not in line with the wider knowledge-economy trend towards more remote/flexible work.

The number of inhabitants per MEP varies from 90,342:1 (Malta) to 878,738:1 (Germany). In national parliaments, the ratio is 6,861:1 in Malta and 115,087:1 in Germany.(2)

The turnover of MEPs after elections is high. It ranged from 43% to 63% between 1979 - 2024. Not only are MEPs obliged to ‘re-apply’ for their jobs every 5 years, but there is also effectively a coin’s toss chance as to whether they will get it.(3) Plus, even if you deliver, because of low name-recognition, voters are unlikely to consider an MEP’s individual track record at the ballot box.

On job prospects, while MEP salaries are higher than most national MP salaries, the joke in some Member States is that Brussels is perceived as lower-status, where – as they say in Borgen – ‘no one hears you scream’; a city for young whippersnappers and old codgers to be sidelined, out of the way of important ‘régalien’ politics. The research certainly suggests Bubble experience is no guarantee of securing future top job domestic jobs.(4)

…and it’s getting harder

The Lisbon Treaty extended Parliament’s competence to 40 new policy areas and paved the way for a decrease in the number of MEPs from 751 to 705.

After a drop under Commission President Juncker, we are seeing a rise in the number of legislative proposals tabled. They are also getting longer, with more amendments to scrutinise.

There are more delegated acts (technical provisions where Parliament has a role); up from 4 in 2010 to 119 in 2024, with a peak of 196 in 2022.

The number of full committees rose from 12 in the first Parliament to 20 today.(5)

All this means that fewer MEPs (and, importantly, their staff) are increasingly expected to develop and exercise deeper expertise in more areas.

You pay peanuts, you get monkeys

This argument could understandably be construed as laughably out of touch. Being an MEP is a privilege. Even with the workload, it is still a plum job with ample benefits and a salary several times the domestic average. But, given their potential to directly impact the lives of 450 million EU citizens, we shouldn’t be aiming for just ‘average’.

Putting aside the ethical argument (public service as a privilege and a calling), there are a few outcomes-linked cases for raising salaries:

Low-salary, high-prestige positions can tend to attract more established, already-wealthy ‘hobbyists’ with good personal networks. A prime example is Jacob Rees-Mogg. His credentials as an eccentric member of the establishment with a blinkered obsession for the anachronistic in no need of a salary are impeccable. His credentials as an effective policymaker, less so.

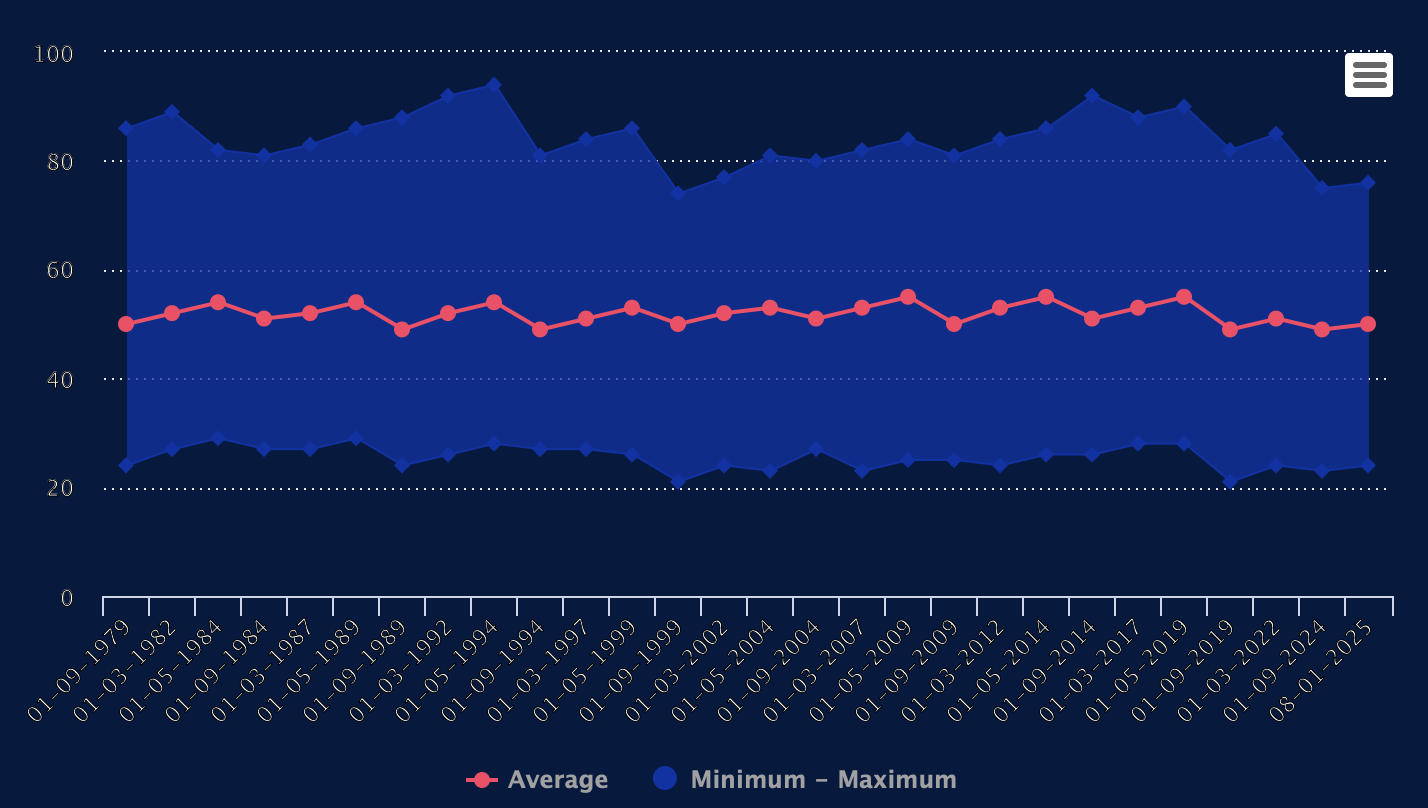

For talented, ambitious young people, the offer of poor job security, high workloads, and dubious career prospects might be possible to offset by higher salaries.(6) Young people provide dynamism to older institutions, arguably have more skin in the game, and have higher risk appetites. Europe needs all three if it is to escape its self-inflicted doldrums. So, it’s a shame the average age of an MEP hasn't budged beneath 50 since the Parliament’s first direct election in 1979.(7)

Average age of MEPs from 1979 - 2025

Experts command a higher price. If the EU must insist on legislating every cutting-edge technology, it should at least make sure its legislators understand and – ideally – have experience at the cutting-edge, rather than just at political manoeuvring. Given how high a salary a skilled software engineer commands in the EU (neverminded the US, never mind stock options) the EU will have to rely on ‘public duty’ arguments to attract engineers, because they certainly won’t do it for the pay or work/life balance.

Conclusion

It's an unpopular agrument, exactly because “people don’t like their politicians to be comfortable … They’d rather you lived in a f*cking cave”. But at some point, if we want to increase the calibre of our elected officials, we must start thinking about novel ways to attract new talent. But I don’t think the public discourse is there yet.

Perhaps a more palatable intermediate step is to increase staff salaries. This will make the Parliament more attractive to a wider pool of talent, and help keep the many young, hard-working, non-hobbyists with some degree of experience and expertise in the system, potentially replenishing our pipeline of talented MEPs in the years ahead.

***

(1) The daily allowance could be the most contentious benefit, but is probably in line with (or maybe even below?) senior business travel practices the private sector. It also appears that, like in private enterprise, that those found fiddling expenses have been reprimanded – including forced repayments and even jailtime.

(2) While they are not the first port of call on constituency questions, MEPs are still contacted by constituents and expected to dedicate some time to parochial issues.

(3) McKinsey famously has the up or out policy, where the lowest performing 5% is fired every six months. Over a five-year cycle, all things equal, you have a better chance of being kept on at the Firm (59%) than being an MEP elected in 2019 and then re-elected in 2024 (37%).

(4) This study finds that the number of MEPs who use the European Parliament as a ‘stepping stone’ into national or regional politics is extremely low. The authors argue it is because of the emergence of a ‘European Political Class’, as EU politics becomes more important and, therefore, more attractive. Another way of reading this is that only a small number of a larger pool of MEP ‘applicants’ are eventually selected for national political election lists or posts. Perhaps – to use the study’s terms – some of those who would rather go back home end up stuck in Brussels (‘Euro Politicians’) or just leave the institution all together (‘One-off MEPs’). These are the top two most common career trajectories for MEPs, according to the study.

(5) To be fair, I am not wholly convinced by this point myself. More committees may not mean more work. Also, the number of temporary staff for the political groups supporting on committee work increased from 147 in 1979 to 1135 in 2019.

(6) The salary for an (entry-level) Associate at McKinsey in Paris is €95K–€112K per year. The average salary for a Partner is €350K. The average MEP is 50 years old, so their comparable salary band is likely to be closer to the Partner than the Associate. Since job security at McKinsey is better than the European Parliament (see (3)), why wouldn’t a young law/politics/business graduate (as many MEPs start out) pick a well-paid career formatting slides then advising clients to ‘cut costs and increase revenue’ over a life of often-thankless public service?

(7) Actually, the fact that the upper limit of the age range has dropped from 86 in 1979 to 76 in 2024, but the average age remains the same probably means that today we have more older MEPs than we did in the 1970s.

- Brendan Moran is Director at DELTA-V Public Affairs